The necktie’s story is long, winding, and surprisingly dramatic. Today it’s the universal symbol for “court, church, or job interview,” but its origins stretch across armies, royal courts, Enlightenment salons, Victorian dandies, industrial offices, and modern wardrobes.

The tie has never been just a strip of fabric. It has served as military insignia, romantic flair, a mark of discipline, a corporate badge, and now—because it’s no longer required—an intentional piece of self-expression.

Let’s follow this curious little accessory from battlefield grit to boardroom polish.

Troops, Turbulence, and the Birth of the “Kravata”

If you want to trace the tie’s roots, you have to leave the boardroom and head straight to the battlefield.

During the Thirty Years’ War in the early 1600s, Croatian mercenaries serving in the French army wore distinctive knotted scarves around their necks. These weren’t fashion statements; they were practical identifiers—colorful cloths that signaled rank, regiment, and national origin.

The French officers noticed the look immediately. Here was a simple but striking accent that added color, individuality, and a bit of swagger to an otherwise utilitarian uniform. The French began calling it la cravate, a linguistic descendant of “Croat.” Croatian kravata is still the modern word for “necktie” today.

And then one very important person took notice: King Louis XIV.

The young Sun King, already developing a lifelong appetite for spectacle, admired the Croatian neckcloths so much that he brought the style into the French court. In a moment, a military identifier became the must-have accessory of Europe’s most powerful elite.

Versailles: Where the Cravat Becomes a Status Symbol

Once the cravat crossed the palace threshold, it evolved quickly from battlefield necessity to courtly extravagance.

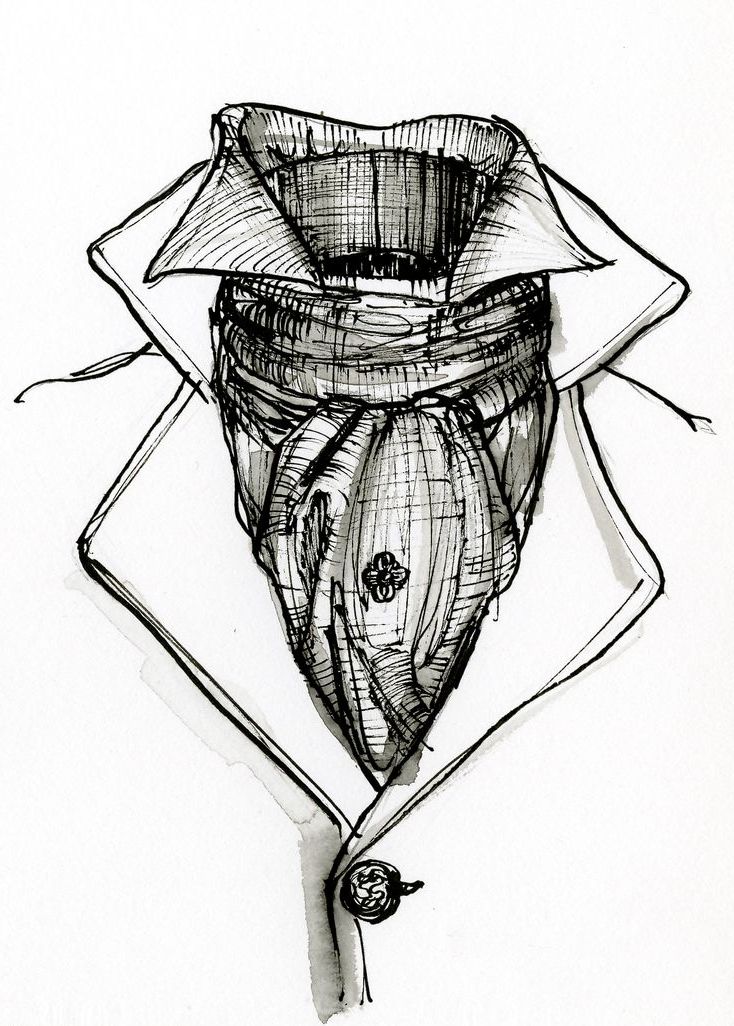

In 17th- and 18th-century Versailles, men of means wrapped their necks in wide, lavish bands of linen, lace, or silk. These were starched, pleated, folded, perfumed—sometimes so elaborate that valets needed special training just to tie them.

Wearing a cravat in this era didn’t say “I’m fashionable.” It said: I have wealth, I have leisure, I have people who dress me. And yes, I would like to be looked at.

France was the trendsetting superpower of Europe, so the cravat spread to London, Amsterdam, Berlin, and beyond. Dressing well became a form of cultural fluency: if you wanted to signal sophistication, you mirrored Versailles.

One notable variation from this era was the Steinkirk, a deliberately disheveled, loosely knotted cravat worn after the Battle of Steenkerque. It said, “I’m elegant, but not trying too hard”—an attitude every modern man can understand.

Enter Beau Brummell: The Man Who Invented Modern Menswear

By the early 19th century, European menswear was still clinging to the remnants of aristocratic flamboyance—powdered wigs, embroidered waistcoats, silk stockings, and bright colors. Then came George “Beau” Brummell, a man who didn’t invent the modern suit outright, but refined it so decisively that everything before him feels like a different language.

Brummell came from a respectable but modest background, yet his intelligence, wit, and eye for detail won him access to the highest levels of London society. When he befriended the Prince of Wales, he found himself at the center of the social world—and he used that influence to redefine what elegance looked like.

Instead of lace, jewels, and colorful fabrics, Brummell championed simplicity, precision, and flawless tailoring. He favored dark coats cut close to the body, perfectly fitted trousers, and crisp white linen shirts. His approach was rooted in restraint: nothing should be loud, everything should be impeccable. A man’s distinction came not from decoration but from the purity of line, cleanliness, symmetry, and fit.

The cravat, which had been decorative and elaborate in the 1700s, became under Brummell’s hand a symbol of refinement. He tied his crisp white neckcloths with such care that it was said he sometimes attempted the knot several times each morning until it met his standards. But even here, the effect wasn’t flamboyance—it was disciplined minimalism. The cravat became a structured, architectural accent rather than a frill.

Industrialization and the Birth of the Modern Tie

By the mid-1800s, society was shifting at a pace the world had never seen. Cities swelled, factories roared, railways connected continents, and a growing middle class stepped into offices instead of battlefields or aristocratic salons. With this transformation came a new kind of daily uniform—one that required practicality, speed, and reproducibility.

The old-style cravat, with its demanding folds, delicate fabrics, and valet-assisted knots, simply didn’t suit the realities of industrial life. A clerk in a London counting house or a businessman riding a steam train from Manchester to Birmingham didn’t have the time—or the patience—to wrestle with starched linen every morning.

This pressure created the conditions for the modern tie to emerge.

From Cravat to Necktie

Neckwear began to evolve toward simpler, more functional forms:

-

The Ascot became the heir to the formal cravat—still elegant, still structured, but easier to manage and popular for daytime events and gentlemen’s clubs.

-

The Bow Tie developed as a compact, symmetrical alternative—perfect for evening wear, where precision mattered more than flourish.

-

And then came the most important adaptation: the long tie, a narrow strip of fabric designed to be looped once around the neck and knotted quickly in front.

This long tie is the ancestor of what we recognize today. It abandoned elaborate folds and embraced directness: clean, vertical, and efficient. Where the cravat often drew horizontal attention across the chest, the long tie pulled the eye vertically—mirroring the increasingly structured lines of jackets and trousers.

The 20th Century: When the Tie Learned to Speak

If the 19th century gave us the modern tie, the 20th century taught it how to communicate. In a single century, neckwear adapted to art movements, technology, global politics, and shifting ideas of professionalism. The tie became less of a requirement and more of a cultural barometer.

Early 1900s: Foundations of Modern Style

As fabric production improved and ready-to-wear clothing expanded, ties became longer, better constructed, and more consistent in shape. This created the clean canvas that the rest of the century would experiment with.

1920s–30s: Art Deco Energy

The Jazz Age brought bold patterns, geometric designs, and richer colors. Hand-painted ties appeared, and the Windsor knot gained popularity thanks to the Duke of Windsor’s sleek, symmetrical style. Hollywood reinforced the tie as part of the aspirational, successful look.

1940s: Postwar Confidence

After wartime fabric rationing, ties re-emerged wider and more expressive. Vivid colors and large motifs reflected a sense of optimism and swagger. Men could change the feel of their entire outfit simply by changing the tie.

1950s–60s: Slim and Modern

Mid-century modernism pared everything back. Ties became slim, subtle, and clean, aligning with the era’s minimalist suits and the younger, sharper British influence. The tie felt modern—straightforward, symmetrical, and confident.

1970s: Wide, Loud, and Unapologetic

Oversized lapels meant oversized ties. Patterns grew bold and sometimes chaotic—paisleys, florals, exaggerated geometrics. Love it or not, the ‘70s tie reflected a decade that embraced maximalism.

1980s: The Power Tie

With corporate culture ascendant, the tie became armor. Strong reds and assertive stripes defined the “power tie,” projecting ambition and authority—especially in finance and politics.

1990s–2000s: The Corporate Uniform

As global business culture standardized, ties grew more conservative: small repeating patterns, simple stripes, match-with-anything solids. Even so, the tie remained a subtle way for professionals to express personality within a rigid dress code. Over the past twenty years you can see the gradual slimming and filling out as Americans went through the skinny tie craze (1.5-2 inches in width at the thickest point) to the more modern standard size (3.25 – 3.5 inches in width at the thickest point).

Conclusion

In the end, the necktie’s journey mirrors our own changing ideas about identity, status, and self-presentation. From Croatian cavalry to French courts, from Brummell’s discipline to the office towers of the 20th century, the tie has always been more than decoration—it’s been a subtle language. And in an era when it’s no longer mandatory, the tie is finally free to be what it was at its best all along: a deliberate choice. Worn well, it adds clarity, intention, and a touch of ceremony to the everyday. Whether you knot one on for a big moment or as part of your personal style, the tie’s long history offers a simple truth—sometimes the smallest details speak the loudest.

If you’re ready to make those details work for you—tie, shirt, and suit all speaking the same fluent, polished language—start the custom process with us today by scheduling a consultation and building a wardrobe that’s tailored to your life, not just your measurements.